The Soft Burden

(Part 3)

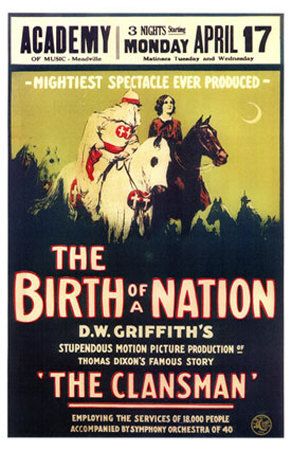

This is where Mom's beliefs and mine come into sharp

contrast. Mom has her pride and her Klan stories, and like so many other people

born into Southern families she dismisses the KKK as some inconsequential thing

from the past. But I am acutely aware that it still exists. A former Grand

Wizard held public office and still makes political endorsements (because

people still listen to him). In Georgia, a branch of the Klan wants to adopt a

stretch of highway for litter cleanup. I see Klansmen as domestic terrorists

who are somehow clinging to outdated beliefs and perpetrating acts of violence

based on a war that, despite the rhetoric of extremists, has been over for a

very long time. But the invalidity of their philosophy does not mean they are

extinct, or even endangered. For me, the Klan is part of a very real white

supremacist movement and an organization that wants to violently tear down one

of the principles I grew up with: equality for all.

|

| (From Wikimedia Commons) |

I am fortunate to be surrounded by people who oppose

hatred, ignorance and violence, and they do it without resorting to hatred,

ignorance and violence themselves. They know their “enemies.” When they protest

Klan or other rallies, they dress up as clowns, relying on distraction and

irony rather than anger. When I was in college in Austin, a few women I knew

went to a KKK rally and asked Klansmen about membership possibilities -- “So

can anyone join? Is there a form to fill out? Can I take some of your

literature home to share with my family?” – which really impressed me, because

the women were Black. I've known other people who oppose the social and

political groups that use patriotism and religion as excuses for hatred – and

rather than protest angrily, my friends pray for these people to find peace and

enlightenment. They have inspired me to do the same.

These are the kinds of people I stand with, but they are

not the kind of people I came from. In a way, counting myself among those who

oppose the Klan and its ilk deepens my shame about my family history, because I

came from a large family full of the kind of people my friends stand against.

By action, I am part of a force against injustice; by blood, I'm the very thing

I oppose. But believing and acting in opposition to the Klan and any other

group that promotes hatred is a possible path to salvation– a way to try to

transcend the past.

I had a conversation about the KKK Quilt with a friend of

mine who's a missionary. I told her how even though I was not a slave owner or

a KKK member I felt a kind of residue from the actions of my ancestors. I told

her the quilt seems like a giant symbol of institutional racism that will

eventually come to me, like some family curse. She agreed that it's a heavy

subject and said she could understand how I might feel like the quilt, and

everything it means, is a burden I have to bear. But then she reminded me of

the story of Nehemiah in the Old Testament and how he prayed for forgiveness

for himself, for his family and for his entire country.

“That kind of thing happened a lot in the Old Testament –

one person seeking salvation for a whole group,” she said.

Then we talked about my great-grandmother, Granny, and

what she might have been thinking when she grabbed the KKK robe and cut it up

into squares to use it for an entirely different purpose.

“She redeemed it,” my friend said. “She turned it into

something new.”

And I suppose she did. Granny took something almost

universally reviled and turned it into something useful -- something with a

connotation of coziness, gentleness, home.

The quilt and I are alike in that no one would ever

guess, just from looking at it, where it came from and what secrets it might

hold. And if the remnants of that hated robe can be redeemed, perhaps I can,

too. What I end up doing with my strange inheritance can help me change how I

view myself and my past. Holding on to it seems somehow unhealthy, but giving

it away seems like a form of denial, and although I feel shame and disgust

about my family's ties to the Klan, I can't deny that they exist.

In the county where Granny lived, there is a small museum

dedicated to the area's history. I think the healthiest thing for me to do is

loan the KKK Quilt to the museum indefinitely, for display or just for safe

keeping. I will tell the curators where it came from – made by the daughter of

one of the county's prominent families – and what it is made of – a symbol of

hatred given a new and gentle purpose.

The museum houses a collection of the pottery made by the

former slaves who ran their own free enterprise after the war. Many of the clay

jugs and bottles on display are still whole, survivors of the nearly 150 years

since their creation. My ancestors' KKK robe, however, is no longer

recognizable. Perhaps putting all these artifacts in the same building can show

that freedom endures, but hatred can be rendered powerless and even be turned

into something comforting. Perhaps, a century and a half after the Civil War,

some of the “general hard feelings” – including my own – can be put to rest.