The Soft Burden

(Part 2)

I remember looking back through the newspaper archives in

the county where my great-grandmother lived and seeing a very brief story about

a young Black boy who had been found “accidentally lynched” in a barn sometime

around the turn of the century. There wasn't much question in my mind about who

might have “accidentally” lynched him, especially after I found out my

ancestors who had lived in that county were part of a thriving population of

Klan members in the area.

The same county was home to the first Black free

enterprise in Texas after the Civil War – a pottery shop operated by the freed

slaves of a Presbyterian minister. This could be taken as a sign of

enlightenment, and the site of the pottery business has earned national

landmark designation. But there are reports of “general hard feelings,” as The

Handbook of Texas put it, and violence against the business owners. I can't

help but wonder if my ancestors ever acted against the pottery owners – if the robe that's now part of the KKK

Quilt was there during any of the post-war attacks on these men who were trying

to become truly independent.

This part of our shared heritage has created quite a few

“general hard feelings” between Mom and me. Mom is unflinchingly proud of our

family's past, but not because of any lingering racism on her part. She is from

the last generation of my family to go to high school before desegregation, and

she used the words “colored” and “Negro” for decades, but when social mores

changed, she changed with them. And, after all, she raised me to accept

everyone as equals and embrace other cultures.

|

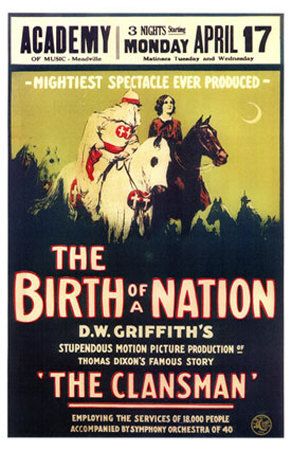

| (From Wikimedia Commons) |

If you ask her about why she holds our Southern ancestors

in such high esteem, she'll simply say, “You have to remember, these men were

fighting for what they believed was right. They weren't right, but it's what

they believed in.”

The last time we had that conversation, I wanted to

respond that the same could be said for the Nazis, but that would have started

a conflagration of a magnitude I was not prepared to deal with. I just shook my

head, letting Mom know that even though I knew I could not change her mind, she

had not changed mine, either.

A couple of years ago, Mom presented me with a special

gift. She had just had one of her prouder moments: attending a rededication

ceremony for a monument to Hood's Texas Brigade, the outfit in which one of our

more prominent ancestors served during the Civil War. She bought me a limited

edition medal struck to commemorate the rededication. The medal came in a

plastic box with a certificate of authenticity that included the words, “May

You Wear This Medal With Pride.” She also gave me a copy of the program from

the ceremony, sure that I would want this souvenir related to one of our

accomplished ancestors. According to the program, the crowd said the Pledge of

Allegiance and also the Salute to the Confederate Flag: “I salute the

Confederate Flag with affection, reverence and undying devotion to the cause

for which it stands.”

What was that cause, exactly?

But Mom didn't care – the important thing to her was the

recognition of our forefathers and their tenacity in fighting for what they

thought was a noble cause. The important thing to me is that I can't wear the

medal she bought me with pride, nor can I salute the Confederate flag with

affection. But filial devotion, and a little joy at seeing Mom become

momentarily giddy, kept me from mentioning either of those points as I accepted

these mementos with a tired sigh.

Mom has even been able to justify our ancestors'

membership in the Klan. She's not the only person who's ever done this, of

course – a friend of mine who has the same sort of background I do said her

grandmother told her that Klan members just put on their costumes and rode

their horses together, as if it were some kind of social club to keep the

menfolk busy while the women were at their knitting circles. Whenever I bring

up the Klan's place in our family history, Mom always stops me in mid-complaint

and says that whatever else it did, the Klan stepped in to see that justice was

carried out whenever a Black man raped a white woman. Somehow I think it would

matter less to them if a white man raped a woman of any color, but regardless,

Mom focuses on the perceived chivalry of the Klansmen, as if they were actually

white knights and not just calling themselves that.

One of Mom's favorite family stories (and her favorite

Klan story) has to do with one of our foremothers: a woman with the improbably

adorable name of Tiny Bell. Tiny Bell's husband died in the flu epidemic in the

early part of the 20th century. At the funeral, in the middle of the ceremony,

the church doors swung open and several Klansmen, in hoods and robes, walked

into the church, found Tiny Bell, and handed her a bag of money. Her husband

had been one of their own, and they had collected money to help support his

widow.

I was surprised to learn that the Klansmen were capable

of such an act of kindness, but I don't think the Klan could assist enough poor

widows or avenge the honor of enough compromised women to save its reputation.

I know the Klan began as a response to Reconstruction. It

was started by men who found themselves suddenly desperate – their fields and

homes in ruin, cities burned, social order destroyed, friends dead or starving,

and a crowd of politicians who seemed indifferent to (if not pleased with) their suffering. But I can't

accept the idea that man's inhumanity to man is reason to carry out more acts

of inhumanity. Hunger is no reason to drag a family out of their home in the

dead of night and whip them. Cognitive dissonance does not give a man the right

to shoot a Black man for not tipping his hat as they passed each other on the

street. And there is no excuse for allowing hatred to expand to include other minority

groups. I can't say I fault Tiny Bell for taking the money the Klansmen gave

her – perhaps it was their way of trying to help her avoid the destitution that

had turned them into what they were, and I have no doubt she needed the money.

But one act of charity – even one that benefited my relatives – is not enough

to get me to ignore more than a century of violence. Instead, in a sense, it makes it worse.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please remember when commenting that manners cost nothing.